Village-scale resilience

The end-of-the-world already happened, it's just not evenly distributed. But with every end is a new beginning.

Roomy - our digital community garden for knowledge cultivation - has taken a long time to get right. Long enough that some people lost faith in us along the way, and that's fair. We'll try our best to earn it back.

A year ago we already had something that worked. Roughly every two months since then we have scrapped what we had and started anew. Never from scratch; we always kept the best bits around, and they've compounded. But new enough that there was no continuity of service. Never something stable enough to start hosting real, living community spaces.

Our partnership with ATmosphereConf marks the beginning of this continuity. No more do-overs. We have a real (pro-bono) customer-relationship to maintain now. The first of many. This changes our mode of development from being architecture-oriented to solutions-oriented. But having taken our time with the former is what will enable us to shine in the latter.

So as we reorient ourselves from the proactive to the reactive, I'd like to linger in this liminal space for just a moment longer and reflect on why this thing took all the time it's taken, and what makes me confident it was worth it.

Local-first problems

The majority of what I'll for simplicity's sake call the Western-World-of-netizens would've been plenty satisfied by a regular server-centric alternative to Discord or Facebook Groups, so long as it was open software and connected to the Atmosphere to resolve the cold-start problem of making a new social network.

I'm one of those westerners, and I designed and founded Roomy to scratch my own itch as an indie game developer and open source organizer.

But from the very beginning, Roomy was also designed for someone else. Someone with materially different needs than me.

Over a decade ago I embarked on a journey to Rashidieh, a mixed but primarily Palestinian refugee camp in southern Lebanon. I spent three months there as a volunteering youth envoy of ‘Palestinakomiteen i Norge’ together with the close friend who had invited me along.

Though it’s referred to as a ‘camp’, Rashidieh is a dense city of brick & cement, housing over 30,000 people. It's the same size as Molde, the biggest city an hour away from my tiny home town. Established in 1936, Rashidieh camp is nearly a century old. As such it is an unusual place with its own flow of time.

I had done this type of longer-term stay abroad a handful times before; a rare privilege afforded to me as a worldly Norwegian citizen. And while I do believe in the genuine altruism of myself and others, these journeys have always been for a selfish reason at heart. An escape; a search.

This time I was searching for meaning in the wake of my mother’s passing a year prior. In the village-community of Rashidieh I was met with heartfelt compassion from people for whom the loss of family members – whole families even – was a brutally regular occurrence of life. There was no comparing my bereavement to theirs, yet we grieved together all the same, and in that grief we were equals.

Excerpted from 'Too late', 12. October 2024

One of the most extraordinary things about communities forced to persevere in extreme living conditions is that they develop bespoke technologies strictly for on-the-ground problems. Out of pure necessity their technological sophistication will in some cases far exceed the stagnant status quo of the so-called Developed World.

Rashidieh is more connected than you might imagine a "refugee camp" to be. Lots of people have mobile phones, and there are quite a few houses with internet-connected wifi routers as well. Still, connectivity remains a luxury. Village-wide disconnections can be caused by anything ranging from accidental power outages to intentional disruptions by oppressive authorities, both domestic and foreign.

My time in Rashidieh was spent (alongside my friend) together with a small family: A mom, a dad and their son. The son was a computer-person. And being the friendly neighborhood supergeek, he was regularly downloading the Internet in a Box and serving it back out to his local-area community via his residential wifi. That way even if they lost access to the outside world for a bit, the locals of Rashidieh could still head over to Muhammad's for the most recent download of everything.

The will and skill is there. All they need is the appropriate toolkit suited to their conditions. Given a robustly designed Community in a Box, the residents of Rashidieh could autonomously maintain a local-area communications network independent of a higher authority. Whenever Rashidieh temporarily loses its connection to the internet they would only be out of reach to the outside world, but not to each other.

Planet-scale solutions

So what does a rural refugee camp in Lebanon have to do with us Westerners?

You know what happens if I lose internet connectivity here in the fancy capital of Norway, Oslo? I'm completely f***ed is what happens. Local-area redundancy networks and backup caches? We have no such thing. No need! We'll always be connected, we're a Developed Country.

Yet it's not that long ago since Portugal had a near nation-wide outage, and even though people still had their satellite-phones as a fallback the comms grid was heavily overburdened and unreliable in that time of "inconceivable crisis".

The closer you look at our digital infrastructure the more you realize it's all hanging by a thread, and it only takes Vlad and Daffodil on opposite sides of the earth to both get sick on the same day for the whole grid to come crashing down.

Our uninterrupted high-speed connectivity is contingent on an energy-blind, self-terminating economy of hyperconsumption. Modern technology and its comforts is premised on the perpetual-growth machinery that has pushed us past our planetary boundary many times over, all whilst transferring wealth upwards.

Most of us may not feel the oppressive thumb of authority pressing down on us as keenly as my friends in Rashidieh do, but it's on our necks just the same. Every essential layer of our digital infrastructure is chiefly owned, operated and controlled by a stack of oligarchic companies in varying degrees of partnership with the state they're holding hostage.

Systemic collapse is everywhere

The end of the world is already here, it's just not evenly distributed.

Sounds like a nihilistic spin on William Gibson’s famous quote, but what I'm saying is a lot of people have already experienced their whole world crumbling and somehow they came out at the other end still standing.

Low-bandwidth, intermittent, lo-fi tech that's peer-to-peer connected, distributed via bluetooth mesh networks and pirate wifi antennas, appears utterly irrelevant until it's suddenly a matter of life and death.

In Iran, a place no stranger to societal whiplash, Briar is keeping people connected at a desperate time when mainstream alternatives are failing them.

The vibe-coded but demonstrably good enough Bitchat is topping the appstore charts in Uganda (turbulent elections) and Jamaica (natural disaster).

A year ago it must still have seemed implausible for the USA communications grid to be turned adversarially against its own populace. Not so much any longer.

We all need connective tech that isn't dependent on centralized authorities and middlemen. We all need tech that's rooted in place, effective at the scale of 1 and up. And we all need tech that exists to everyone's proportional benefit, not an elite few.

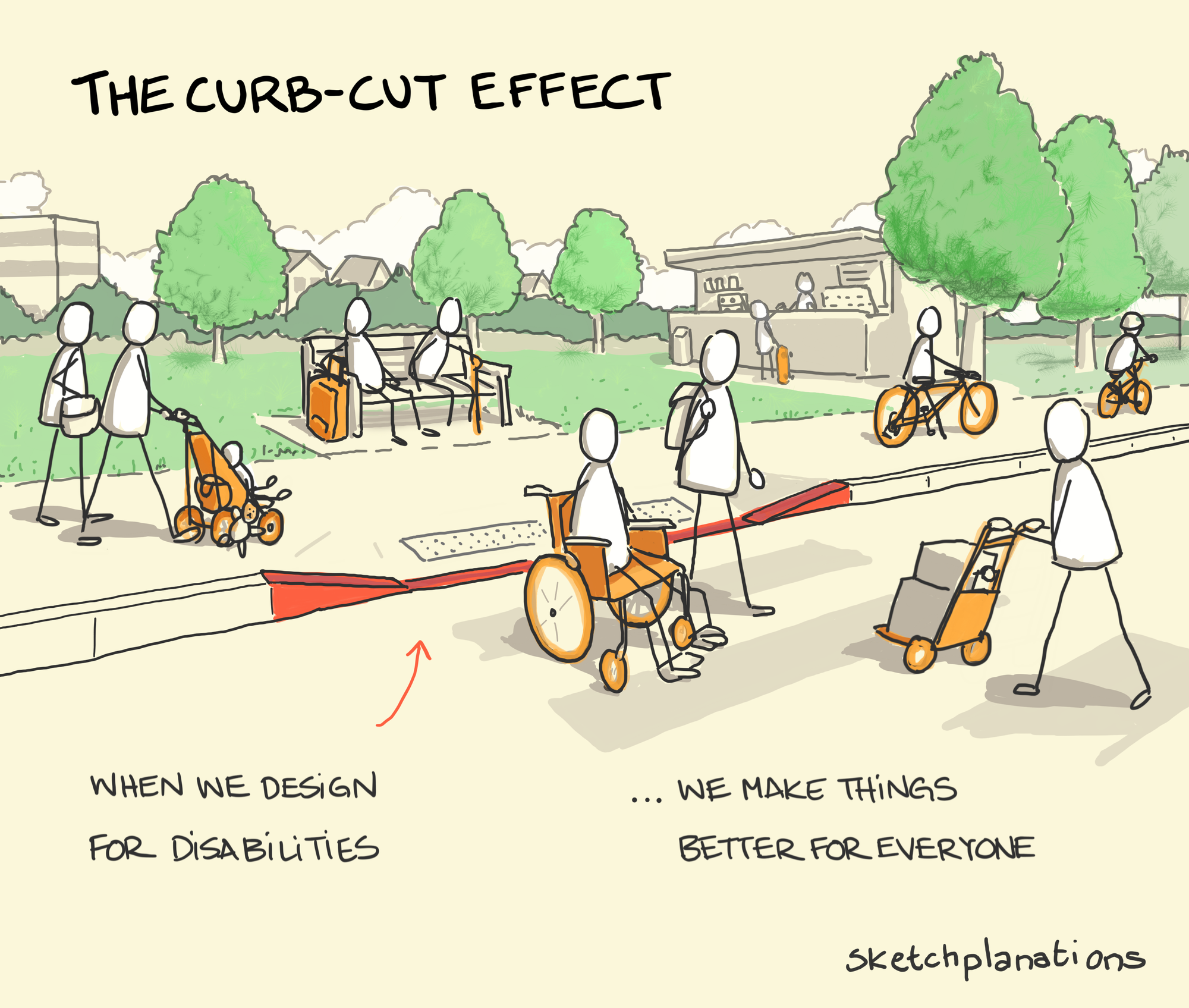

Much like the curb-cut effect showing how universal design starting from the needs of the marginalized benefits everyone, the necessary affordances of a liberatory technology are largely the same no matter what part of the planet you're living on.

Designing for interbeing

Unlike Briar and Bitchat (unaudited), Roomy is not security-first but rather community-first.

Your local libraries and community gardens optimize for accessibility, not defensibility. So too with the type of space-making Roomy exists to facilitate.

Briar is part of the medicinal treatment of a sick democracy; Roomy is preventive care. Though conversely, I can think of few things more aggressively anti-fascist than massive crowds of diverse people congregating in shared, loving spaces.

We need both secure and accessible means of social congregation, and they're by no means mutually exclusive. But businesses want intranets and nerds wanna hack on cryptographic locks, leaving scarcely any money and attention left for cozy open-access spaces on the web.

That needs amending, we thought, so we built Roomy with a really solid foundation for locally adapted, decentralised, malleable communications that is sufficiently performant for users today. It can't do the fanciest p2p mesh-net stuff yet, but we are architecturally prepared and pointed towards that eventuality.

We're an idealistic bunch, but the best way to build a local-first app is to first build any kind of app commercially successful enough to sustain its ongoing development.

In the meantime we have already achieved cloud-independence by participating in the Atmospheric Computing movement as an Open Social application with sufficiently self-sovereign data storage.

The AT Protocol behind it all originated from many of the same peer-to-peer ideals mentioned herein, but the best way to make an impact with their flagship app Bluesky was to build a widely accessible web app.

We like that strategy and are following suit to complement their networked feeds for mobilization with our intertwined spaces for organisation.