Company as a Commons

What if excess wealth derived from business couldn't be privatized? Through the levers of steward-ownership, companies can protect their purpose-oriented long term mission from the maligned incentives of absentee stakeholders.

Let's talk about business practice as a net-good within the commons, as opposed to an external extractor of it.

I've previously alluded to our ambitions to build a non-extractive, post-growth company:

Weird has since been subsumed by Roomy to become 'Roomy Persona', our community platform's (B2B) equivalent of a Discord Nitro (B2C).

To recap, while I appreciate that a company like Bluesky did its very best to protect the laudable values and vision of its founders, there's got to be a better alternative to the prevailing company-formation model than what they've earnestly admitted results in The Company inevitably turning adversarial towards its own product and values in the long term.

While I find any company that has taken tens of millions in VC money innately unnerving, I doubt there was any other way for Bluesky to build a desperately needed offramp for X/Twitter in time for the mass migration that consequently happened, so I commend them for navigating those perilous waters as best they could.

That said, I don't fully agree with this statement:

> Businesses live & die on a shorter timeline than people

That's only true in the modern era, especially for tech companies. There's a reason why we've got a whole bunch of people walking around with last names like 'Carpenter' and 'Mason'. Kongō Gumi famously existed independently for nearly 1500 years before it finally succumbed to modern capital pressures.

So while I agree with the general strategy of designing products and ecosystems under the assumption that their commercial benefactors are "possible future adversaries", it must not be considered an inevitability, lest it become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

A tech company with the longevity of IBM (113yrs old) but the ethical backbone of Patagonia is possible.

That inquiry has led me to the concept of steward ownership. (Update: In October 2025 I distilled the essence of these ideas into a 3-minute talk titled Your self as a future adversary.)

The most profound act of corporate responsibility for any company today is to rewrite its corporate bylaws or articles of association in order to redefine itself with a living purpose rooted in regenerative and distributive design and then to live and work by it.

~ Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics

Rather than being resigned to a story of "company as a future adversary", we can utilize the framework of steward-ownership to reify our vision for "company as a future commons".

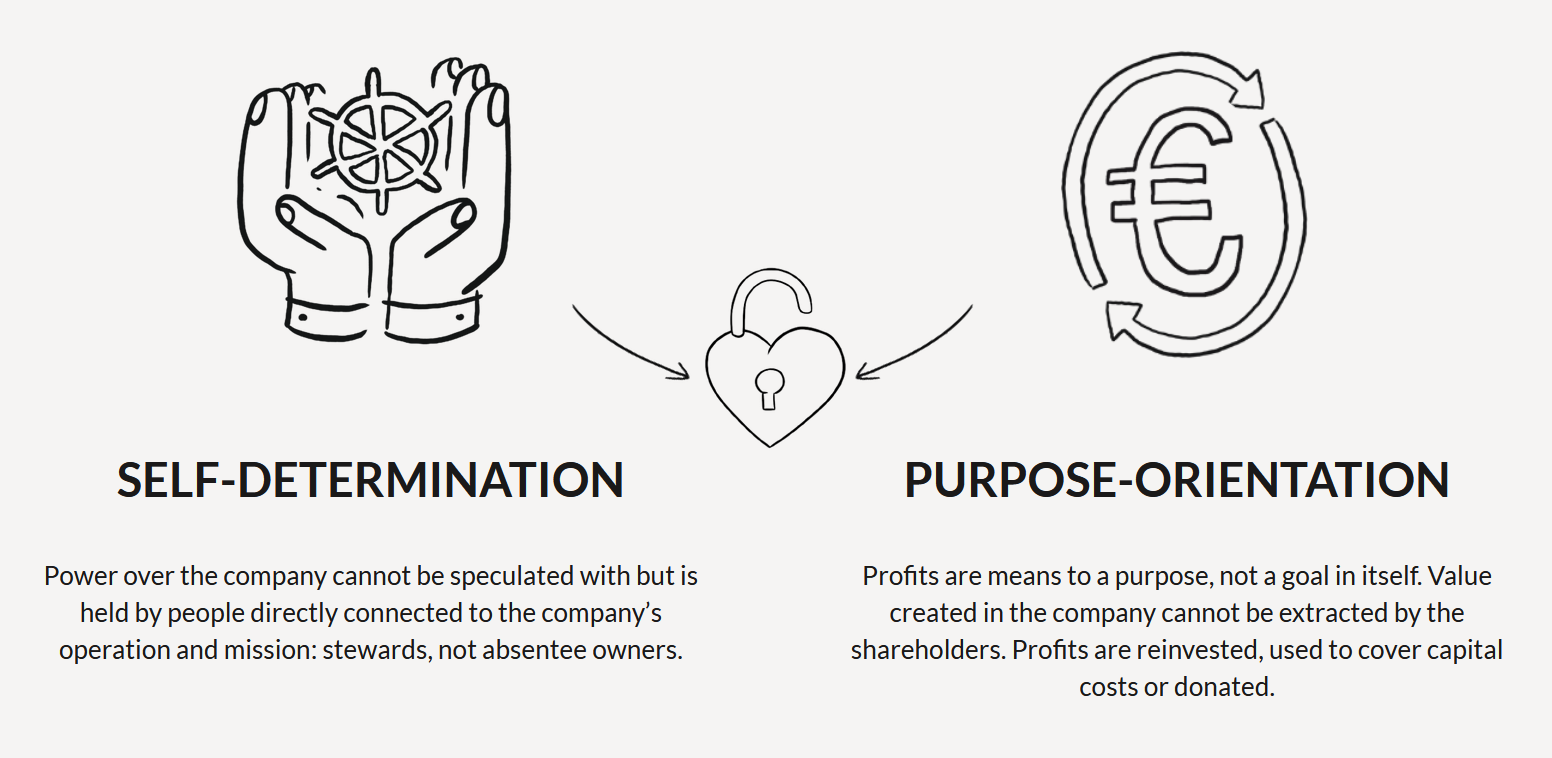

Steward-ownership is about structuring a company in a way that separates economic rights (to money) from voting rights (to decision-making power). These models have been tested in modern forms for over a century.

Often structured as trusts, foundations, or employee-owned companies, all of these companies have fundamentally redefined ownership by committing to two principles:

(1) Self-governance — Control remains inside the company with the people directly connected to stewarding its operation and mission, not external investors or absentee owners. With the control of the company held in a trust, it can no longer be bought or sold.

(2) Profits serve purpose — Wealth generated by these businesses cannot be privatized. Instead, profits serve the mission of the company, and are either reinvested in the company, stakeholders, or donated. Investors and founders are fairly compensated with capped returns/dividends.

Considered an alternative to the destructive paradigm of shareholder primacy, steward-ownership can be implemented using various legal forms depending on the type of company and jurisdiction. The less established the legal framework, the more creative one needs to get.

The concept of “steward-ownership” harnesses the power of entrepreneurial for-profit enterprise, while preserving a company’s essential purpose to create products and services that deliver societal value and protecting it from extractive capital.

Business for Purpose

Unlike a coop or a Public Benefit Corporation which can be acquired or redesignated, the principles of a steward-owned company are binding in the long-term.

The distinction is made painfully clear in the case of the well-intentioned social network Waxy:

Their founding charter as a PBC ambitously stated "in the strongest possible legal terms" that:

1) Ello shall never make money from selling ads;

2) Ello shall never make money from selling user data; and

3) In the event that Ello is ever sold, the new owners will have to comply by these terms.

Ello exists for the benefit of the creative community, and we will never serve ads or sell personal data.

Spoiler at the end of the article:

Despite their idealist manifesto and their Bill of Rights, I don’t believe they could ever truly be in partnership with their community once they were taking large amounts of venture funding. All of their ideals and big dreams were easily undone, even the legal restrictions they defined in their Public Benefit Corporation charter:

1) Ello made money from selling ads to third parties;

2) Ello made money selling their user data to a third party;

3) Ello was sold, and the new owners didn’t comply with those terms.

We've got to do better than that. Surely we can do better than that!

Just like other forms of equitable and participatory co-ownership, steward ownership is not a silver bullet. Yet it leans heavily toward broad rather than narrow power distribution and legally preempts the most common predatory tactics of the hypercapitalized global marketplace.

Meaningful change requires us to address the fundamental structural deficiencies of our system, by rethinking the goals and incentives that guide decision-making in companies. We need to ask ourselves: who holds power and what is motivating their decisions? To create new solutions that harness the potential of capitalism (entrepreneurship, innovation, competition, a decentralized economy) and move beyond its failures (greed, consolidation, inequality), we must challenge one of the fundamental paradigms of capitalism: the understanding and definition of corporate ownership.

Over the last two centuries, there have been two main mechanisms allocating corporate ownership: (1) buying/selling a business and (2) family succession/inheritance. The former sells the “steering wheel” of the company to the highest bidder, the latter passes it to heirs. These have been the two primary mechanisms of capital and ownership-allocation: the principles of (1) money and (2) blood. The corresponding motivational mechanisms have been profit-maximization and wealth building. In this paradigm, a company is something you own and your objective is to profit from it.

(...)

In Denmark, the combined market capitalization of steward-owned corporations represents 60% of the entire value of the Danish stock marketindex. Studies from Copenhagen University and Yale University with data from Danish foundation-owned (=steward-owned) companies show that foundation-owned companies have a higher survival probability than conventionally-owned companies. While other conventionally-owned companies have survival probability 10% after 40 years, foundation-owned companies have a 60% survival probability over the same period. In addition, foundation-owned companies have a higher employee retention rate and pay higher wages, while at the same time being similarly profitable as non-foundation-owned companies. Foundation-owned companies also have a strong reputation among consumers.

Steward-ownership not only enables companies to better internalize externalities, it also helps combat the growing wealth gap and inequality caused by inherited wealth accumulation. Because steward-owned companies cannot be inherited, they help prevent dynastic wealth accumulation. What’s more, they prevent owners from siphoning rent off of businesses. Instead, steward-owned companies are “self-owned.” These businesses belong to the commons, serving their purpose and all stakeholders who contribute to their successes and helping to create a more equitable, regenerative economy. Capital is in this sense democratized.

Mainstream examples include Patagonia (US), Mozilla (US), Sharetribe (Finland), Novo Nordisk (Denmark), Ecosia (Germany) and Bosch (Germany). They're not all prime exemplars of post-growth enterprises, but they're still far more transparent and democratically run than their respective peers.

For a modern take we can look to Vyld, a biotech company fom Germany established in 2021. As a producer of women's health products made of seaweed it was paramount for Vyld that their company was as good as their product.

It just doesn’t make sense to produce a great, sustainable product, but

then have an exploitative company structure and culture.

Instead of going the easiest route with VC capital that expects 10x-50x hypergrowth across 5-8 years for an equal or bigger ROI multiplier, they opted for far more limited amounts of capital from investors supportive of incremental growth and a fixed (e.g. 3x cap) return on investment, without giving away any voting control in the company. This way Vyld cannot be bought up by P&G only to be relegated to green-washing in a megacorp.

Steward-owned Roomy corp.

Steward Ownership isn’t yet a box you can check off with ease, though in a few select locations that will soon change thanks to persistent pioneers in the Netherlands and Germany. (Exhaustive Summary)

For most places still it’s more like a voluntary self-certification of equitable co-ownership.

Implementing this in my home country of Norway (and possibly also in the US, depending on how strange our geopolitical situation gets in the coming months) is going to require novel Articles of Association that set us up with a public commitment towards an ‘exit to steward ownership’, closely related to the notion of 'exit to community'.

Documents like this blog post are part of that public promise. Another one is our Values page.

What do we work for:

We work cooperatively to enrich The Commons, in service of the global community.

Why we do the work:

The Commons[1][2][3] is what sustains us and our communities, so enriching it is to enrich our selves and those in our localities (digital or otherwise) in an ecologically sustainable manner.

In much the same way that Patagonia is obligated to reinvest its profits into the environmental ecosystem it extracts from, Weird inc. (or Roomy corp.) is obligated to reinvest its profits into the commons, primarily in the digital realm by funding its open source dependencies.

Any investments into our venture (our first modest angel investment will be announced shortly) will only be accepted on the condition that our path towards becoming a fully steward-owned company is unimpeded.

We think the commons-owned company is the scarcely discussed middle way.

Here we are, anguishing over whether we should relinquish what little remains of our shared resources to Big State or Big Capital, meanwhile there was a third, much less hazardous alternative available to us all along. Well, not so readily available just yet, but this form of collective ownership can quite literally be imagined into being if only we believe in it enough to write our own rules for a fairer game that isn't predicated on top-down authority.

Further Reading

And a topic for another day: Regenerative Economics ♻️